Planning and management of urban green spaces for temperature mitigation

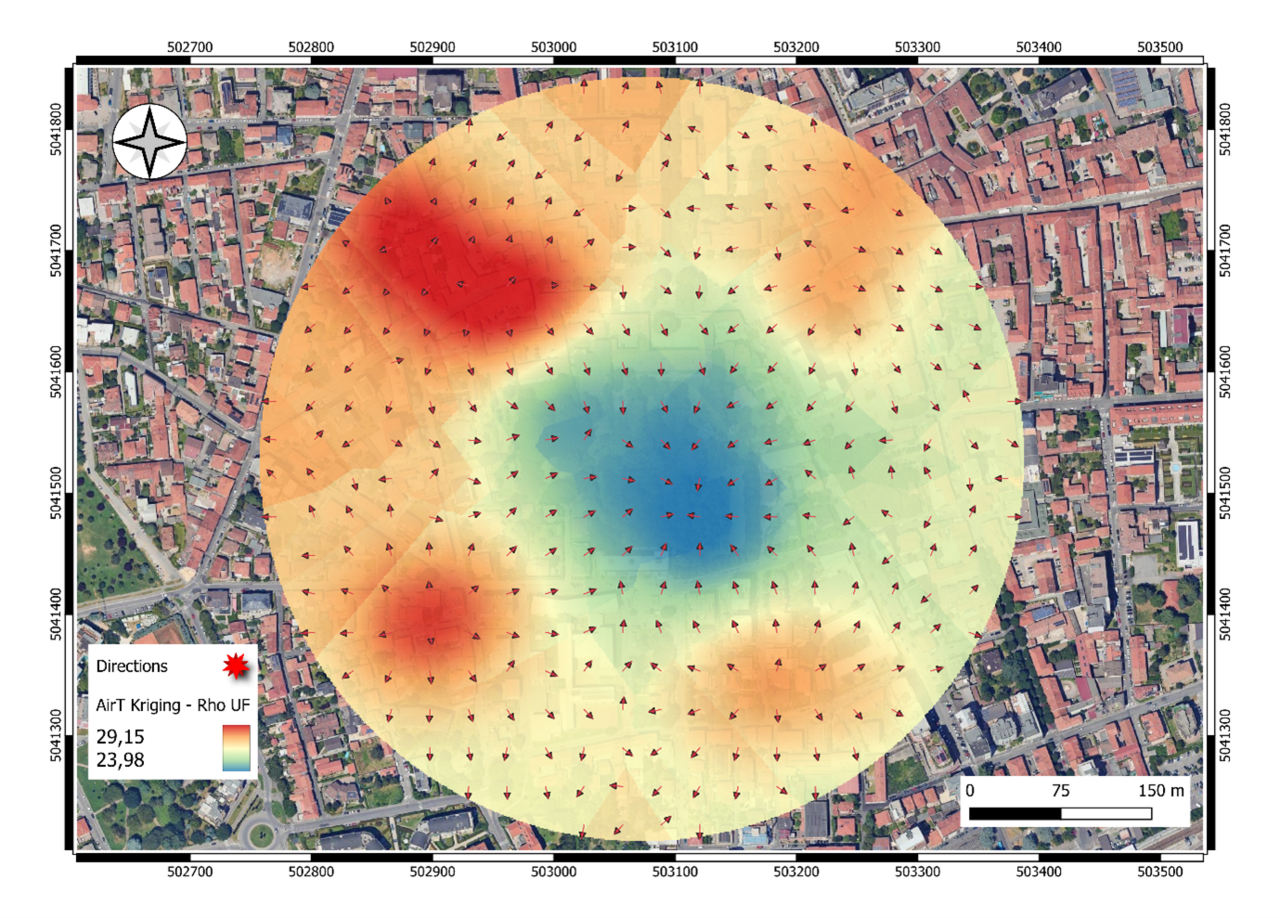

Kriging of temperature around Rho Urban Forest, Villa Visconti-Banfi.

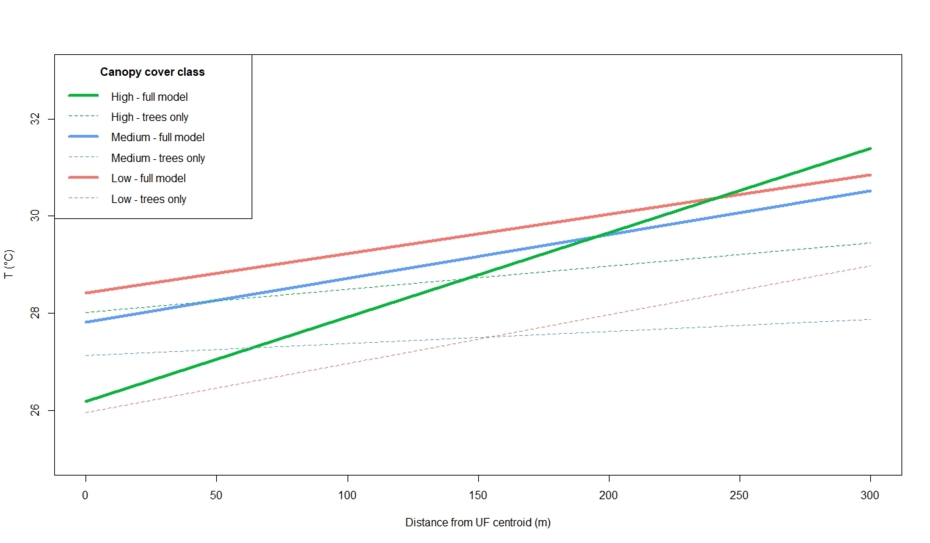

Recent studies (Saini et al., 2025) show that an urban forest of size between 0.75 and 2.5 ha provides a temperature mitigation effect of max 180 m radius around the plot centre and that this effect is more dependent on forest canopy cover density than upon urban forest size. This has important implications in an urban environment where it could be easier to increase the canopy cover of an urban forest than to increase its size.

Context:

Most European cities are characterized by highly fragmented green infrastructure, composed of small parks, tree-lined avenues, and residual patches of vegetation. Yet even small urban forests (Considered here as a patch of urban greening including public parks and private gardens or villas, that compound to around 1 Ha) play a crucial role in moderating local microclimates through shading and evapotranspiration, while also providing co-benefits such as carbon storage, air pollutant removal, and stormwater retention. Their efficiency depends not only on total area but also on canopy cover, vertical structure, and spatial distribution. Increasing canopy density within existing green areas often provides greater heat mitigation benefits than expanding their footprint alone, offering a cost-effective strategy where land availability is limited.

Urban greening supports multiple policy priorities at the EU level, including the EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change, the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030, and the Nature Restoration Law. Many European cities are already implementing tree-planting programs and climate-resilient planning frameworks, yet these efforts face constraints linked to land value, maintenance budgets and governance fragmentation. Evidence-based approaches that quantify the cooling reach of urban forests can help optimize investments, enhance social equity in access to green spaces, and strengthen resilience to future heat extremes.

Expanding urban canopy cover also reinforces citizens’ connection to nature, fosters outdoor well-being, and strengthens the shared identity of European cities as sustainable, liveable environments.

Problem Description:

Across European cities, increasing frequency and intensity of summer heatwaves are amplifying the impacts of the urban heat island effect. Dense urbanization, widespread soil sealing, and the loss of vegetation have made many metropolitan areas particularly vulnerable to extreme heat. Average temperatures in major European cities have risen by more than 2 °C compared to the late 20th century, while the number of heatwave days continues to climb. These conditions elevate heath-related mortality and morbidity, increase energy consumption for air conditioning, aggravate air pollution, and heighten health risks, especially among elderly and low-income residents who have limited access to cooling green spaces.

To mitigate extreme temperatures in an urban environment, more widely distributed and denser urban forests are needed, instead of a few larger forested areas. This is to be considered when planning and building green areas inside every city. The main problem is that, although denser forests are better at mitigating extreme temperature, the maintenance cost is generally higher, and such a forest might be seen as not attractive, generating less engagement and general social backlash due to concerns about safety or illumination. This could lead to the green area abandonment or misuse.

Implementation Steps:

The practice consists in planning, designing, and managing a diffuse network of small and medium-sized urban forests that optimize temperature mitigation and human comfort. It combines spatial analysis, participatory planning, and targeted greening interventions to expand canopy cover where heat reduction potential and social needs are highest.

Steps for implementation:

Generate a map with existing green areas and classify management units.

- Use GIS shapefiles to identify all urban green spaces larger than 1,000 m², including parks, schoolyards, and underused public land. Categorize them by canopy cover, surface permeability, and surrounding land use.

- Model the spatial cooling effect.

- Apply a circular buffer of ~180 m radius around each identified park centroid to represent the mean air-temperature mitigation reach observed in empirical studies. - Merge overlapping buffers to visualize the cumulative cooling footprint across the city.

- Analyze climatic and environmental variables.

Integrate local meteorological data to identify prevailing wind directions and urban heat hotspots using high-resolution temperature or satellite data (e.g., Sentinel-2 LST or NDVI).

- Identify priority intervention zones.

- Overlay heat exposure maps with the buffered green areas to locate neighborhoods with limited cooling influence, high population density, and social vulnerability.

- Locate suitable land for new green areas.

- Within these priority zones, identify vacant or convertible plots (e.g., disused lots, parking areas, brownfields) suitable for afforestation or park creation, considering ownership and accessibility constraints.

- Design new green areas for optimal canopy cover.

- Plan new or expanded green spaces with medium to high planting density and mixed structure (trees, shrubs, herb layer) to ensure strong microclimatic effects. Favor native, drought-tolerant species with high transpiration capacity

- Implement planting and early maintenance.

- Conduct planting during the dormant season (autumn–early spring) with proper soil preparation and mulching. Ensure early maintenance (watering, pruning, replanting failures) for at least three years.

- Integrate social and institutional participation.

- Establish a local stakeholder network (including residents, schools, NGOs, and municipal services) to co-manage and monitor the new urban forests, ensuring long-term care and equitable access.

- Monitor and evaluate effectiveness.

- Deploy low-cost air temperature sensors or mobile apps to monitor local cooling performance and vegetation growth. Use the data to refine future planning and communicate results to citizens and decision-makers.

Stakeholder Engagement:

Co-designers of the good practice should include research institutions, universities, and urban planning authorities working together to integrate scientific evidence into city-scale green infrastructure design. Stakeholder engagement is essential from the outset, involving local administrations, environmental agencies, NGOs, and citizen associations to co-produce knowledge and ensure social acceptance. Implementers may comprise municipal technical services, landscape architects, and forestry contractors responsible for planning, planting, and maintenance. Beneficiaries are the residents who experience improved thermal comfort and well-being, as well as the broader community engaged through citizen science initiatives - such as participatory monitoring of temperature, vegetation growth, and biodiversity.

Knowledge Types:

Scientific knowledge underpins the methodology through empirical data on air temperature mitigation, canopy structure, and spatial modelling derived from field sensors and statistical analyses. Practical knowledge from urban foresters, planners, and landscape managers guides species selection, planting density, and long-term maintenance. Local knowledge contributes to identifying priority areas and ensuring social acceptance, as residents share insights on microclimatic discomfort and neighbourhood use patterns. Finally, co-produced knowledge emerges through participatory monitoring and citizen science, combining technical data with community observation to inform adaptive urban greening strategies.

Replicability:

YES, the practice has been tested and replicated in multiple contexts and scales and therefore, can be easily transferred and/or adapted to other initiatives with similar goals.It was not actively replicated on purpose, but many Urban Forests are dense (mostly private green areas in general) and they can demonstrate their mitigation potential everywhere.

Key Success Factors:

Climatic urgency and policy alignment

The growing intensity of urban heatwaves makes the expansion and densification of urban forests an urgent adaptation measure. Integrating this practice into municipal climate action plans and the EU Nature Restoration Law ensures long-term political and financial commitment, enabling continuity beyond project cycles and coherence with broader environmental goals.

Tangible public and health benefits

The visible cooling, improved comfort, and better air quality generated by increased canopy cover create direct, perceivable benefits for citizens. These outcomes strengthen public support, motivate community participation, and contribute to reduced health risks from heat stress—key drivers for maintaining social legitimacy and engagement.

Cost-effectiveness and technical feasibility

Compared to large new parks or blue infrastructure, the creation of a diffuse network of medium- to high-density green areas is less costly, easier to implement, and suitable for compact urban environments. It uses existing land parcels, standard urban forestry techniques, and locally adapted species, ensuring economic viability and replicability across cities.

Common Constraints:

- Higher management and maintenance costs: increasing canopy density and vegetation complexity requires greater maintenance efforts, especially in the first years after planting, and coordination among municipal services. This was addressed through the creation of multi-actor maintenance agreements, including local associations and volunteer networks, and by promoting low-maintenance, drought-tolerant native species to reduce long-term costs.

- Initial social resistance to change: early opposition sometimes emerged due to perceived loss of open space or limited awareness of climate benefits. Transparent communication, participatory design workshops, and citizen science activities helped demonstrate the local cooling benefits, fostering acceptance and long-term stewardship.

- Mitigation to green area misuse or neglect: unmanaged or poorly monitored green areas can face vandalism or low social use. This was mitigated by integrating design-for-safety principles (lighting, visibility), organizing regular community events, and creating co-management models that involve residents, schools, and NGOs in monitoring and care activities.

Lessons Learnt:

- Dense urban forests maximize climate and health benefits.

Increasing canopy cover and vegetation density significantly enhances temperature mitigation, improves local air quality, and supports biodiversity. High-density planting is a cost-effective adaptation measure that strengthens ecological resilience while directly improving citizens’ thermal comfort and overall well-being.

- Edge densification with internal clearings optimizes multifunctionality.

Planting denser at forest edges and maintaining a central open area balances microclimatic performance with usability. This design supports strong cooling effects at the perimeter while preserving accessible spaces for recreation, education, and social interaction.

- Long-term social acceptance is essential for success.

Municipal administrations should invest early in communication, participatory planning, and continuous engagement with citizens. Co-design processes, school programs, and community monitoring initiatives foster a sense of ownership that ensures sustained care, appropriate use, and lasting public value of urban green areas.

Positive Impacts:

- Improved local climate regulation and/or cooling

- Improved recreational value

- Improved societal support

- Increased human health and well-being

The main impacts were evaluated through a high-resolution monitoring network of 169 temperature sensors installed around nine urban forests in the metropolitan area of Milan and operated continuously for 15 months (June 2023–September 2024). The study used standardized statistical approaches, including ANCOVA and piecewise regression, to quantify the magnitude and spatial extent of air temperature mitigation under different canopy cover levels. The analysis revealed a significant cooling effect extending up to 180–200 m from forest centres, with maximum reductions of 3.5 °C in mean and 5.5 °C in maximum daily temperature during summer months. (Saini, M., Ovando, G., Colla, L., Vacchiano, G., 2025. Mitigating urban heat: Spatial reach of cooling effect in nine urban forests of Milan. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 114, 129158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2025.129158)

Negative Impacts:

- Increased disturbance risk

The main negative impact identified is the increase in management costs and efforts associated with higher canopy density and vegetation complexity. More intensive maintenance is required during the first years after planting to ensure tree survival, control invasive species, and manage irrigation. These additional costs are temporary, as maintenance needs and expenditures typically decrease once vegetation becomes established and self-sustaining. Over the long term, the benefits of improved thermal comfort, biodiversity, and public well-being outweigh the initial costs, especially when management is shared among municipal services, local associations, and citizen volunteers

Media

- Planning & Upscaling

- Social & Stakeholder

- Urban and peri-urban forests

- Landowners & Practitioners

- Planners & Implementers

- Policy Actors

- Climate change mitigation

- Other protective and regulatory functions

- Social and cultural values

- Mediterranean

- Italy

- Environmental

- It has been studied in 9 urban forests of Milan, for a total area of around 15 hectares of urban green spaces. The total area of Metropolitan Milan is 157 500 hectares. Not implemented yet by our knowledge.