1.2 Assessment of Landscape Context

All forest restoration sites sit within wider landscapes of nature, forests, agricultural lands, villages and so on. The activities implemented on restoration sites influence its surroundings, nature and people, in multiple ways. That’s why it is crucial to look beyond your site boundary when planning and implementing restoration. A landscape is a socio-ecological system, composed of both biogeographical premises and past and present human interactions. It is subject to internal forces, such as natural dynamics and succession, as well as external forces like climate change. Such a broader context should be evaluated from ecological, socio-cultural and socioeconomic viewpoints. In this way, projections on risks and opportunities for sustainable development can be assessed.

Landscapes come in all shapes and sizes, and the scale that matters most depends on the specific issue – whether it’s the needs of certain animal or plant species, the type of human activity taking place, or how the forest is being managed. Landscapes may have a single, a few, or several land cover types. Forest landscapes are dominated by forest land, but can also have other landcover types intermixed, such as water bodies and grasslands. The transition zones, i.e. the forest edges, typically provide important ecological functions including filtering, buffering, energy flow, and preserving biodiversity.

Forest landscapes can form naturally or be shaped by human activity. Natural forest landscapes are often remote areas that have seen little or no human use, or they are the small remaining patches of original forests. In contrast, human-shaped (or artificial) forest landscapes have been influenced by forestry or other types of land use. In Europe, most forest landscapes fall into this second category, reflecting a long history of human impact. Still, large-scale ecological recovery towards natural or semi-natural conditions can be found in places like the Foothills forests of the Scandinavian Mountain Range (the Scandinavian Mountains Green Belt) while elsewhere old-growth and primary forests persist in only fragmented patches.

Across Europe, forest landscapes exist along a wide gradient of management intensity. Intensively managed forests, like age class ones with few tree species, support less biodiversity than old-growth forests. However, if these remnants of original forests are surrounded by intensively managed stands, the ecological processes they depend on, such as natural spread and migration of species, may be hindered.

To assess a forest landscape, you need a clear view of focal species, habitat or issue, i.e., which will help you to define and understand the context. In general, assessments should include spatial distribution of core attributes, such as land-cover types, natural vs. artificial forests, high conservation value forests, successional states, native tree species, tree species mixture, presence of biodiversity attributes such as dead wood, vertical and horizontal heterogeneity, etc. Of specific relevance is the distribution of Annex 1 habitats. Annex I habitats are natural habitat types of community interest whose conservation requires the designation of special areas of conservation. These habitats are listed in Annex I of the EU Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. More info here. Special attention should also be given to other strictly protected areas and areas that are subject to continuous cover forestry or other alternatives to industrial and rotation forestry. Ecological connectivity can be seen as an overall indicator: when it is satisfactory, it ensures natural spread and migration of species, as well as integrity of ecological functionality, even under climate change. Connectivity also matters for other key aspects of forest landscapes – for example, ensuring access for recreation, or safeguarding transition zones such as riparian forests (forests adjacent to water bodies and areas linking forests with other land-cover types.

Related resources

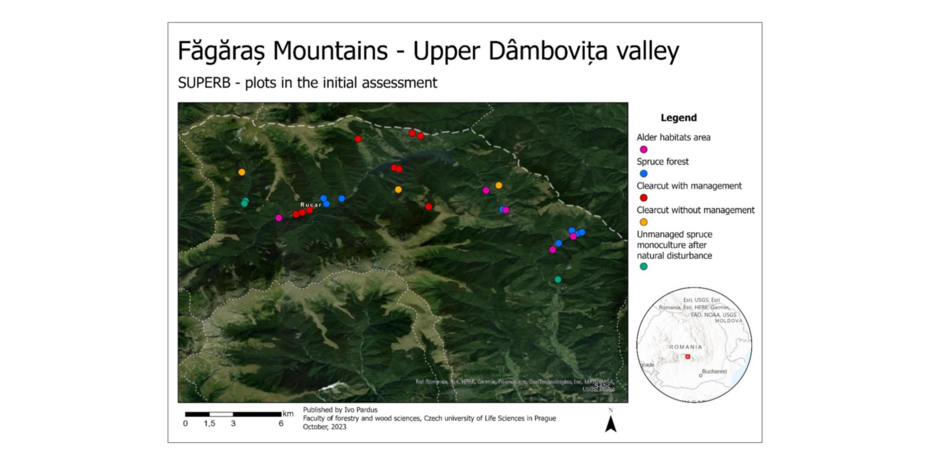

Assessment of initial situtation of restoration areas

Assessment of initial situation is a monitoring protocol that describes setup design and methodology used to assess the current state of forest before applying any restoration measures.

Assessment of initial success and restoration efforts

Assessment of initial success and restoration efforts is a monitoring protocol that includes qualitative and quantitative assessment of early stages of restoration success (1-2 years after establishment) and efforts made to achieve a successful restoration.