4.1 Adaptative forest management

Adaptive Forest Management (AFM) is a practical, iterative approach to manage forest restoration in the face of uncertainty. It’s based on the principle of learning by doing — adjusting actions based on evidence and experience. For those involved in planning and implementing reforestation, AFM offers an effective framework to improve restoration success over time.

Forests are made up of slow-growing, long-lived organisms — trees — that develop over decades or even centuries. This biological reality stands in sharp contrast to the fast-paced changes in climate, land use, societal demands, and economic conditions. Restoration efforts must reconcile this mismatch: managing ecosystems that change slowly in a world that changes rapidly.

AFM helps bridge that gap. It treats forest restoration not as a on-off intervention but as a long-term, adaptive process. Planners start with clear goals — like increasing biodiversity or building resilience — and implement strategies such as reforestation, invasive species removal, or habitat improvement. Outcomes are tracked using indicators like species composition, forest structure, and carbon sequestration. When results deviate from expectations, actions are re-evaluated and adjusted accordingly.

Monitoring isn’t only about collecting ecological data. It also involves staying tuned to social and economic dynamics — community needs, policy shifts, and market trends — that may affect project direction. This broader view ensures restoration remains relevant and effective over time, while also helping to build knowledge that benefits future projects.

Importantly, adaptive management involves people. Local communities, landowners, and public agencies hold a stake in restoration outcomes. A well-designed stakeholder engagement process strengthens decision-making by bringing diverse perspectives into play, which enhances transparency, supports shared understanding, and builds legitimacy for decisions, especially when adjustments are needed.

Despite its advantages, AFM is not without challenges. Institutional unwillingness, funding gaps, and weak and incomplete monitoring can restrict its success. Overcoming these hurdles is key to unlocking the full potential of adaptive management in reforestation — across both landscapes and decades.

Related resources

Modeling assisted migration to adapt forests to climate change

At a six-day summer school in Traunkirchen, Austria, researchers and participants explored assisted migration as a strategy to help forests adapt to climate change. Hosted by BFW with EVOLTREE and CZU, the program combined modeling, genetic diversity and hands-on fieldwork, highlighting practical tools to guide climate-resilient forest management.

Rise from the ashes

The Castilla y León SUPERB demo in Spain focuses on restoring forests to improve brown bear habitats whilst involving local communities. Measures include thinning dense pine, boosting oak acorn yield, replanting burned areas, and grafting chestnuts. Balancing ecology and rural needs, it shows promising paths for coexistence and resilience.

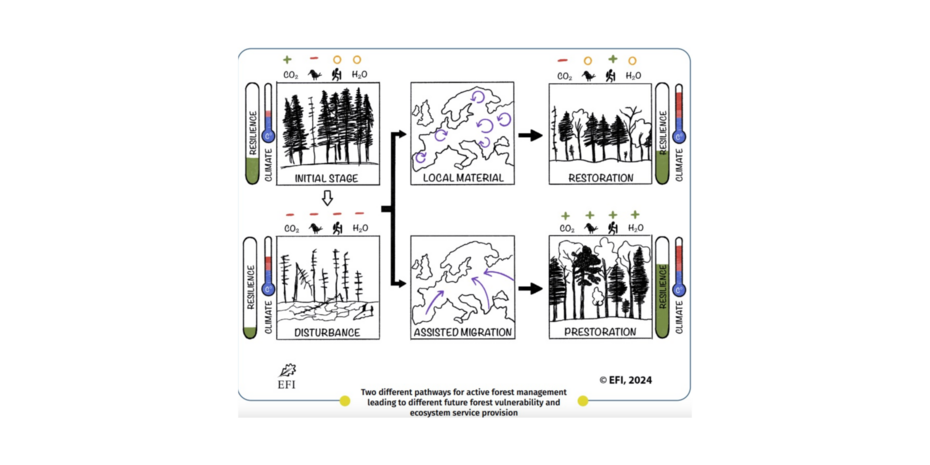

How to strengthen the European forest carbon sink through prestoration: integrating active restoration and adaptation

Active forest restoration combined with assisted Active forest restoration combined with assisted migration (prestoration), i.e. using always the climatically most suitable European tree species and populations, has the long-term potential to enhance carbon sequestration significantly compared to restoration efforts without assisted migration.

Integrative approaches

The Integrate project final report by the European Forest Institute’s Central European Office presents research on integrating biodiversity conservation into forest management. It analyzes forestry impacts, trade-offs, and multifunctional forests, offering cross-border scientific and practitioner insights to support informed policy and practical decisions in Central Europe.