Policy Actors

5.1 Adapting policy to respond to environmental and societal change

One of the main drivers of forest degradation is environmental change. Across Europe, shifts in climate and biological disturbance regimes - including storms, fires and forest pests - are significantly altering forest ecosystems (see for example this forest restoration talk discussing how wildfire behaviour is changing in the mediterranean). This means that the conditions forests experience today will be very different tfrom the conditions they experience as they mature. Moreover, beyond environmental changes, forest and environmental policymaking needs to adapt to changing societal structures and demands for forest ecosystem services.

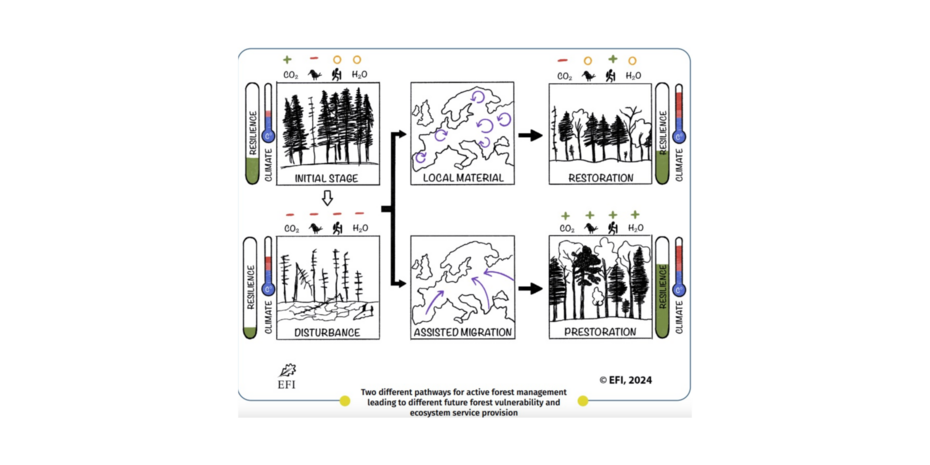

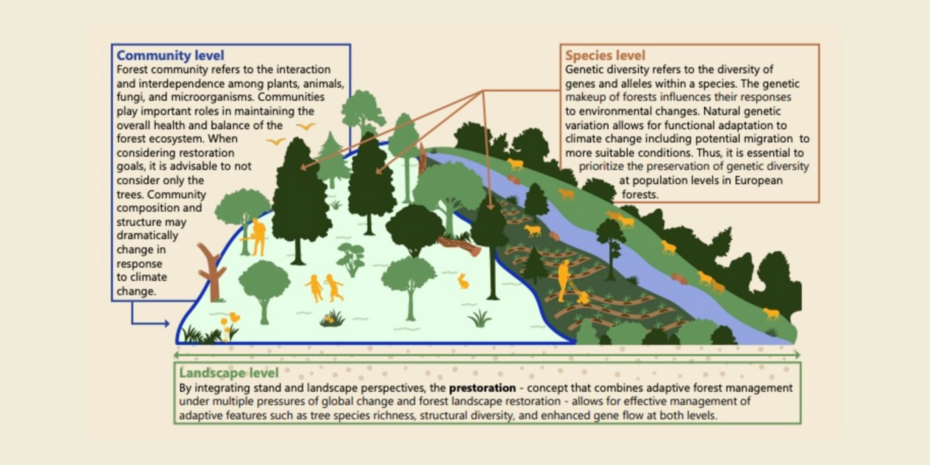

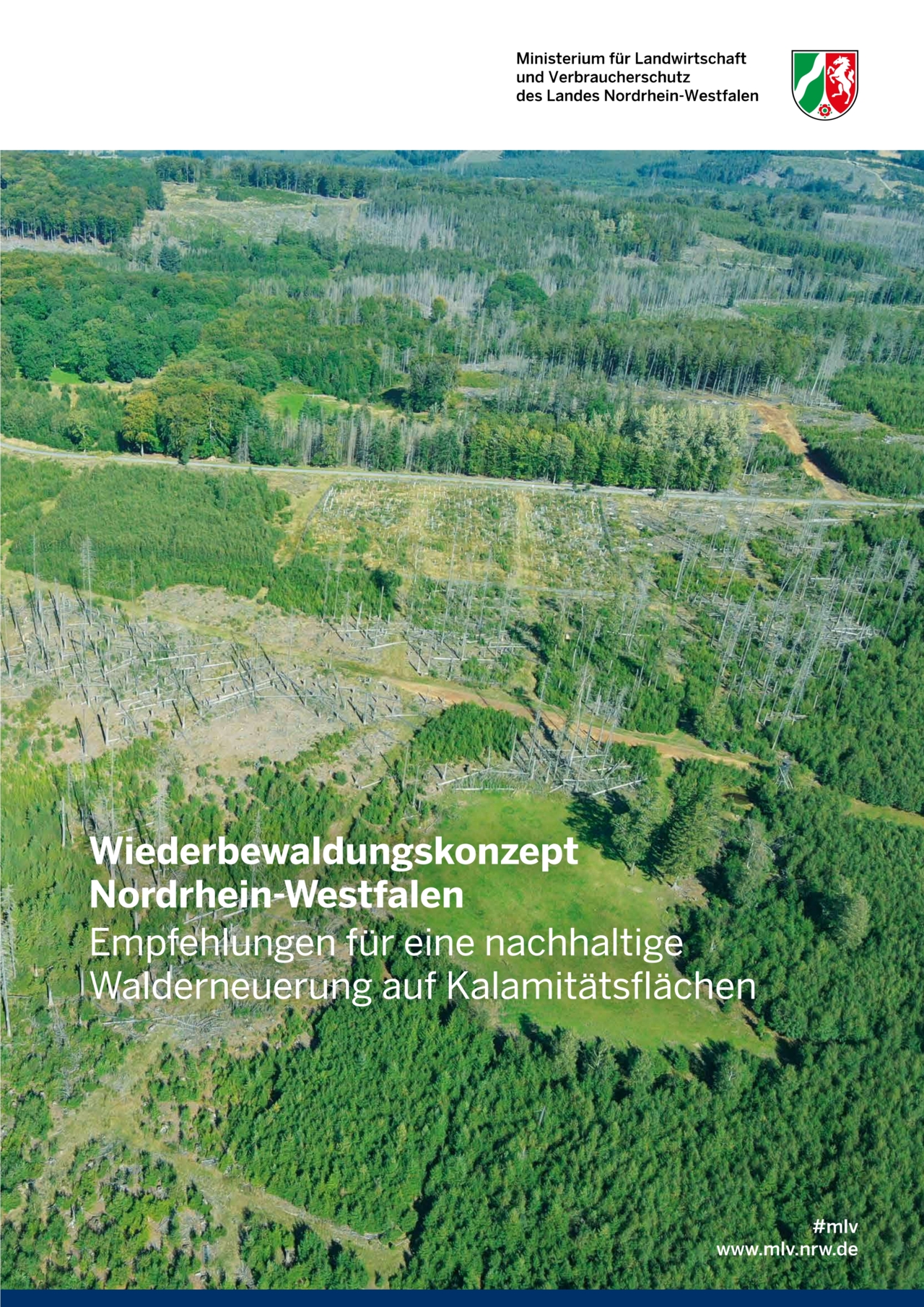

This Knowledge pathway explores the implications of this from a practical perspective. The EFI Policy Brief 11, for example, covers the concept of prestoration, advising for more adaptive forest management practices that build on practical experience and predictions of future conditions (see the EFISCEN – Space model, modelling forest responses to future conditions). The demonstration work in North Rhine Westphalia and the Czech Republic following the bark beetle outbreak explores this in considerable depth (see the Reforestation Concept of SUPERB’s NRW demo). Valuable insights into diverse societal perceptions of forests, their benefits and specific forest restoration practices across Europe can be found, for example, in the study Exploring societal perceptions of forests, ecosystem benefits and restoration.

You as policy actors therefore also need to ensure that policies are adaptive and appropriate to future environmental conditions and changing societal demands rather than simply reflecting past practice. This is challenging given the long timescales involved and given the uncertainty and complexity of interacting factors. It is particularly important to specify success criteria, indicators, or targets that reflect future climatic conditions and evolving societal needs rather than historic conditions (see the SUPERB’s Policy recommendations for the EU Nature restoration Law).

Most importantly, policies need to be designed to incorporate the adaptive capacity of forest ecosystems – for example through the use of more flexible secondary legislation or orders. This can also be done by building strong monitoring and evaluation processes, or by anticipating exceptional cases (i.e. conditions within which the policy will and will not apply). In this regard, assumptions and models used as evidence for policy development must always be clearly stated.

There are tools that can assist in the exploration of options for a more adaptive future and forward-looking forest management (eg. Seed4Forest), and for assessing the coherence of policies across forest-related policy areas (eg. Methodological Framework for Policy Coherence Assessment). Policymakers can also learn from the experience of demonstration areas – especially if those areas have developed upscaling plans or route-maps (Guidelines for the Development of Upscaling Plans) - which can ensure that ‘bottom-up’ learning is incorporated into policy decisions.

Related resources

How to strengthen the European forest carbon sink through prestoration: integrating active restoration and adaptation

Active forest restoration combined with assisted Active forest restoration combined with assisted migration (prestoration), i.e. using always the climatically most suitable European tree species and populations, has the long-term potential to enhance carbon sequestration significantly compared to restoration efforts without assisted migration.

SUPERB’s Policy recommendations for the EU Nature restoration Law

SUPERB aims at large scale forest restoration in Europe, combining scientific and practical knowledge to drive actionable outcomes. This policy brief is based on the concepts underpinning this approach and provides four recommendations for changes to the proposed EU Nature Restoration law.

Seed4Forest

Seed4Forest is a Europe-wide decision-support tool that guides users in selecting climate-resilient tree species, species mixtures, and provenances for forest restoration and management. It integrates up-to-date scientific models—including species distribution, productivity, mixture suitability, and provenance guidance—to assess the performance of multiple species under current and future climate conditions. By combining species- and genetic-level information, the tool enables spatially explicit analysis and supports evidence-based adaptation strategies, such as assisted migration.

EFISCEN-Space model

EFISCEN-Space is an empirical European forest model that simulates development of forest resources. The model is used to assess and evaluate most likely trajectories of future forest development including sustainable forest management regimes, wood production possibilities, trade-offs between different forest ecosystem services under alternative management regimes and climate change.

Methodological Framework for Policy Coherence Assessment

This methodological framework enables forest restoration stakeholders and policy makers to assess the coherence of forest restoration policies and practices with the objectives of other forest-related policy areas. This can support the identification of trade-offs and synergies to inform the planning and implementation of forest restoration (policy) initiatives.

Exploring societal perceptions of forests, ecosystem benefits and restoration

This study examines how people in different European regions perceive and engage with forests and restoration. Through interviews in Sweden, Scotland, Germany, Serbia/Croatia and Spain, it reveals contrasting views of forests and shows that past restoration focused mainly on biodiversity and hazard mitigation, overlooking other benefits. The findings highlight the need for inclusive restoration that reflects community values and societal attitudes.

Climate impacts on wildfires regimes in European forests

Fire behaviour changes, forest projections and implications for forest restoration. Marco Patacca talked about fire disturbances in Europe and how climate impacts wild fire regimes affecting European forests. He dived into the past, explaining how fire regimes have historically developed and elaborated on future projections and what that means for restoration.

Reforestation Concept of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

North Rhine-Westphalia’s reforestation concept focuses on restoring forests after bark beetle devastation to improve biodiversity, capture carbon and to combat climate change. By planting mainly native trees and selected introduced tree species, including through natural regeneration, it enhances forest ecosystems, prevents soil erosion and supports sustainable land use. This helps create healthier environments, cleaner air and recreational spaces, making the region more resilient and sustainable.